Rethinking Browsing: The Agentic Shift

Why the next evolution of the internet begins at the very first step

Welcome to AI Fyndings!

Some shifts in AI arrive loudly. Others begin in places we barely notice. This week’s change sits inside the browser, the tool we use without thinking. It is starting to anticipate our intentions, highlight options and complete small tasks before we ask for them.

This edition is a little different. Once a month, we pause the weekly roundups and focus on one defining shift in AI, unpacking it with a little more depth and clarity.

In Perspective: Let’s look at why this shift matters and why the tension between Perplexity and Amazon signals the first real faultline in an internet where agents begin to make decisions before we do. Agentic browsing turns the browser from a passive doorway into an active guide, shaping what we see and how we move through the web.

By the way, since it’s Black Friday, a few of our AI products are offering some crazy deals this week. If you’re exploring new tools, these might be worth a look:

Kaily (Conversational AI agents) → 25% off Growth and Business annual plans (use code BF25)

Boltic (AI workflow automations) → Pay for 6 months and get 6 months free (use code BF50)

GlamAR (AR try-ons) → 15% off on all plans (chat with sales to redeem)

Pixelbin (AI image editor + text-to-video) → 30% off Lite and Pro plans (use code BF30)

Upscale.media → 30% off annual subscriptions (use code BF30)

We have spent so much time discussing what AI can do for apps and tools that we’ve almost ignored the place where everything actually starts. Not the model, not the app, not the workflow. The browser.

For years, the browser has been the most simple part of the stack. You open it, search for something, click through a few links, compare a handful of options, and eventually find what you were looking for. It doesn’t actively guide the journey or filter the choices. It just keeps the pages in front of you.

That mental model is breaking. Slowly giving way to something new.

You can see signs of this in the day-to-day interactions most of us overlook. You search for a product and instead of juggling ten tabs, the browser brings back a few strong options, sometimes with a clear “best pick” based on price, reviews and delivery time. You look for a place to stay and it quietly pulls from Airbnb, Booking.com and Expedia, cleaning up the noise into something you can skim in seconds. You try to track a package or renew a subscription and the right status or form fields appear before the page has fully loaded.

At first this looks like a natural evolution of “smart features”. We already have auto-fill, ad blockers, extensions that compare prices and search results that summarise half the web for us. None of that feels like a turning point. It’s still you, clicking through, making choices, doing the work.

The important shift is more subtle.

When people talk about agentic browsers, they’re not talking about a slightly smarter Chrome. They are talking about a browser that can listen to an intent like “Find the best monitor under ₹20,000 that ships this week and buy it” and then handle the messy steps in between, from discovery to purchase.

With traditional browsers, your flow looks like this:

You think of a goal → you search → you scan → you click → you compare → you decide → you act.

With the agentic version, it looks more like this:

You state the goal → the browser interprets → it searches, scans, clicks, compares, decides → and then it presents you with the final product choice or a ready-to-checkout page.

The effort hasn’t disappeared. It has just moved. The decision-making process shifts from your hands to the logic of an agent.

Tools like Perplexity’s Comet, Atlas, Fellou and others are explicitly built around this idea of turning the browser into an “action engine” instead of a passive window.

So what is truly new here?

Not that tasks are automated. That has existed for years in the form of scripts, RPA and individual apps.

The difference is that the agent sits at the browser layer, understands intent in natural language and can work across almost any site you use, from ecommerce to travel to admin tools, without each of those sites designing a special integration first.

This is the backdrop that makes the Amazon and Perplexity conflict so telling. What looks on the surface like a policy violation is actually the first real friction between two very different ideas of how the web should work.

Perplexity’s Comet browser takes the agentic idea literally. You tell it what you want, and it doesn’t wait for you to click through Amazon like a regular shopper. It navigates for you. Comet logs into your account, looks at products, compares sellers, weighs delivery times and can even move toward checkout, all while appearing to Amazon like any other Chrome user browsing the site. To Perplexity, this is not a loophole. That’s the entire point. A browser agent should behave like an extension of the user, not a passive observer.

Amazon has an entirely different perspective on this.

Their retail media business depends on the idea that people browse. Not briefly, not efficiently, but deliberately and repeatedly. Sponsored listings, recommendation rails, comparison grids, cross-sells, delivery bundling, Prime nudges are all designed for a human moving through the interface step-by-step. When an agent slices through that flow and jumps straight to the “best option,” Amazon doesn’t just lose a click. It loses the surfaces that make the business work.

So when Perplexity’s browser began completing transactions on Amazon without flowing through the usual steps, the conflict surfaced quickly.

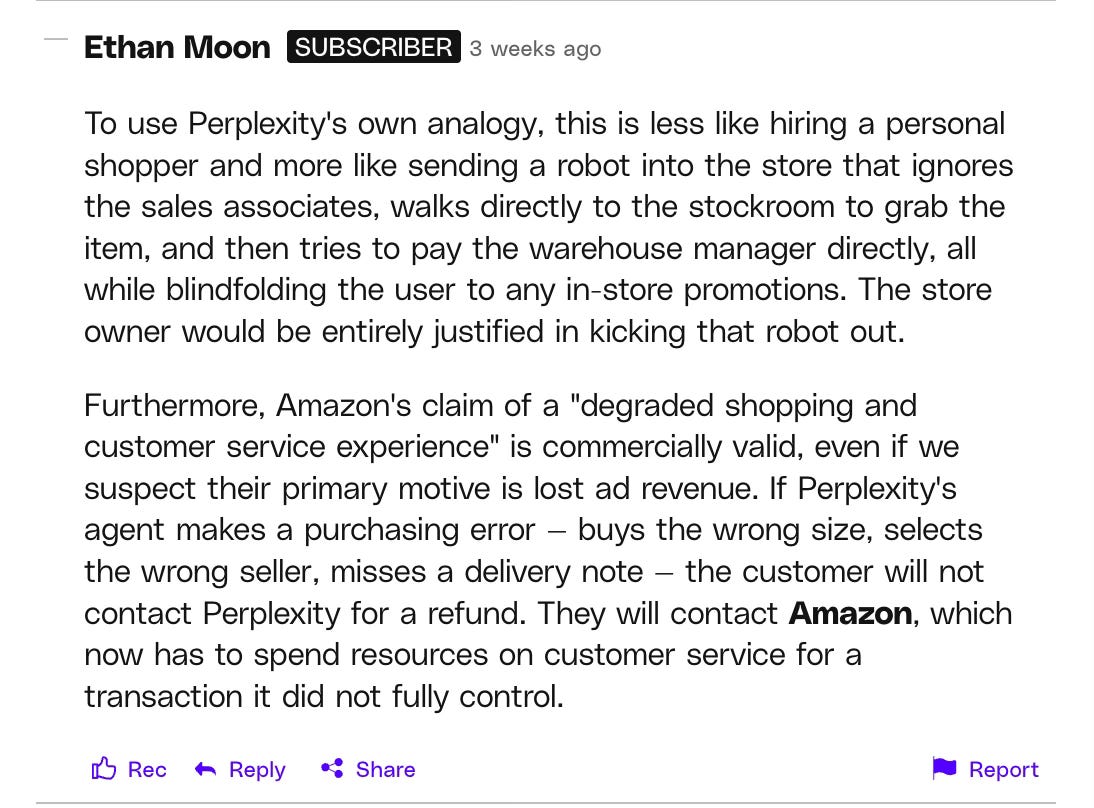

Amazon argued that the agent was bypassing essential layers of the experience and that it cannot guarantee trust or safety if an external system manipulates its flows. Perplexity argued that the user should decide how they prefer the journey to unfold. What appeared on the surface as a policy disagreement was, in reality, a clash between two visions of the web. One sees the agent as the primary guide. The other sees the platform as the central gateway.

Behind the statements, the disagreement is simple: Who should be in charge of the journey? The platform or the agent?

For Amazon, the journey is the product.

For Perplexity, the journey is unnecessary friction.

And this is where the conversation becomes bigger than two companies. If agentic browsers take off, they chip away at the assumption that users will dutifully follow each platform’s designed path, including the filters, the sort options, the comparison modules, the ads, the nudges, the endless “You might also like.” Those steps were built for a world where the user is present at every click.

An agent isn’t present in the same way. It sees those layers as backend details. Its job is not to browse but to deliver an outcome.

For big platforms that rely on people browsing, for example Amazon, DoorDash or Ebay, agentic browsers feel threatening. These platforms are built on the idea that users will look around, compare options and spend time around the experience. That is where ads, recommendations and upsells/cross-sells live. When an agent skips that entire flow and goes straight to the final step, the platform loses the chance to influence the decision. The Verge calls this the “DoorDash problem,” where an agent treats every platform as just a delivery system in the background, not a place with its own design, incentives or brand.

For smaller brands, the impact is a mix of good and challenging. On one hand, an agent that truly works for the user might consider sellers that it would normally take several scrolls to discover. Which means smaller players could actually get more visibility if they offer better pricing, faster delivery, or when their product matches the user’s needs more precisely. This could be the exact shade of olive green a user searched for instead of the generic khaki at the top, the wide-strap sandal the user actually wants rather than the narrow version at the top of the page, or the soft cream fabric chair instead of the bright white one favored by the algorithm. But on the other hand, the competition doesn’t disappear. It simply shifts. Instead of trying to appear on the first page of a platform’s search results, brands may end up trying to appear in an agent’s shortlist of “trusted” or “reliable” options, a list the user might never see or fully understand.

That shift is already visible in how different competitors respond. Alibaba’s AI Mode embraces agents rather than resisting them by integrating agentic flows directly into the marketplace, where early data shows substantial gains in orders and supplier activity. OpenAI’s Atlas and Fellou approach it from the consumer side, building browsers that can act across logged-in sites. Microsoft’s FARA-7B sits even deeper, operating the entire computer interface instead of just the web layer.

Taken together, these developments point to the same idea: the browser is turning into a worker, not a window.

There are real advantages to agentic browsing. For everyday tasks, such as comparing prices, planning a trip, renewing a subscription or checking a delivery, an agent can remove a lot of the small steps that slow us down. It makes the internet feel easier to use, especially for people who find complex interfaces confusing or don’t speak the platform’s primary language. And for businesses, especially in operations, sourcing and internal workflows, these agents can handle the manual work that usually takes hours. They can review documents, compare suppliers, summarise contracts, coordinate schedules and pull data from scattered tools.

But more autonomy also means more places where things can go wrong. A browser that can act for the user can also be misled. Some early studies have shown how malicious websites can trigger unintended actions by feeding misleading instructions to the agent. A browser that autofills forms can accidentally share sensitive details. An agent that completes a purchase could be nudged toward an untrustworthy seller because the page structure subtly manipulates its inputs. And even when nothing malicious is happening, there’s still a question of judgement. When should an agent step in and act for you, and when should it stop and ask first?

This is not theoretical. Security teams at major companies are starting to warn that agentic browsers expand the attack surface. Traditional browsing limits the damage because a human still reviews each step. With agentic behaviour, the browser may act first and the user only notices later. The same autonomy that streamlines the experience also creates room for mistakes, misinterpretation and manipulation.

As these tools grow, the industry will need safeguards, clearer permissions and transparent logs that show why the agent made a particular choice.

Microsoft’s FARA-7B model tries to solve this by adding “critical points” – moments where the system must pause and get your approval before doing something important. Agentic browsers will need their own version of this, or they risk acting too quickly on things the user would have handled more cautiously.

Another concern is transparency. When an agent chooses one seller over another, we need to know why. Was it the price? Delivery? Reliability? Partnership incentives? Something in the training data? Without clarity, we risk replacing platform-driven influence with agent-driven influence without understanding either.

Which brings us back to Amazon and Perplexity. Their conflict isn’t about Chrome spoofing or terms of service. It’s more about who gets closest to the user’s intent – the platform or the agent.

I see this moment as a turning point. Not because of who is right, but because of what the conflict represents. We are moving into a phase where the most influential part of the online experience may no longer be the platform or the content, but the agent interpreting both.

If agentic browsing continues to grow, companies will need to rethink how they reach users and how they build trust. Users will need to understand how their agents decide and what those decisions are based on. And somewhere in the middle, new rules will need to emerge to protect fairness, choice and transparency.

For now, we are only at the beginning. But the Perplexity and Amazon clash shows how quickly this shift is becoming real. When the browser starts thinking for the user, the stakes rise for everyone involved. The next few years will show whether agentic browsing becomes a helpful companion, an invisible filter or the new gatekeeper of the web.

In the Spotlight

Recommended watch: Perplexity vs Amazon: The AI Agent War Begins

I found this episode really interesting as it makes the Amazon and Perplexity clash easy to understand. It highlights the important details, from Amazon accusing Comet of posing as Chrome and bypassing things like delivery bundling and curated shopping signals, to Perplexity’s CEO pushing back with his now public “Bullying is not innovation” letter. It makes the tension clearer and shows how agentic browsing is beginning to challenge the logic behind large platforms.

“AI agents have an adverse effect on advertising. It all leads to a return on ad spend that’s very unusual.”

Closing Notes

That’s it for this edition of AI Fyndings. From agentic browsers starting to shape our online decisions, to Amazon and Perplexity revealing the first real tension between platforms and AI agents, to new tools experimenting with autonomy across search, commerce and everyday workflows, this week was about intelligence quietly moving into the spaces we once assumed were neutral.

Thank you for reading. See you next week with more stories, tools and ideas shaping how AI continues to redefine how we explore, choose and interact with the digital world.

With love,

Elena Gracia

AI Marketer, Fynd