From Manual Work to Assisted Execution

This edition looks at how Octolane keeps sales in sync, Firecrawl extracts data, and Spacely refines spaces.

Welcome to AI Fyndings!

With AI, every decision is a trade-off: speed or quality, scale or control, creativity or consistency. AI Fyndings discusses what those choices mean for business, product, and design.

In Business, Octolane tries to reduce CRM work by following sales activity where it already happens, in email and calendar.

In Product, Firecrawl uses AI to sit between intent and code, helping teams explore web data before committing to full scraping pipelines.

In Design, Spacely focuses on iteration over output, letting designers work through a space instead of generating a final image upfront.

AI in Business

Octolane: CRM That Tries to Keep Up With Sales

TL;DR

Octolane is an AI-first CRM that reads activity from Gmail and Calendar to update deals and draft follow-ups automatically. Reduces manual CRM work, but still needs close review and doesn’t fully replace traditional systems.

Basic details

Pricing: Free plan with paid plans starts from $49/per seat/month

Best for: Sales teams that operate primarily through email and calendar

Use cases: Creating automatic deals, drafting follow-up emails, keeping CRM data updated with minimal manual input

When was the last time your CRM actually reflected what was happening in your inbox?

That doesn’t usually happen. Deals move forward in emails and meetings, but the CRM lags behind unless someone goes back and updates it manually. That gap isn’t dramatic, but it compounds. Follow-ups get delayed. Pipelines lose accuracy.

Octolane helps deal with that lag by connecting to Gmail and Calendar, tracking your activity, updating records in the background, and drafting follow-ups for review. Instead of treating the CRM as a place you visit, it treats it as something that stays in sync with how you already work.

What’s interesting

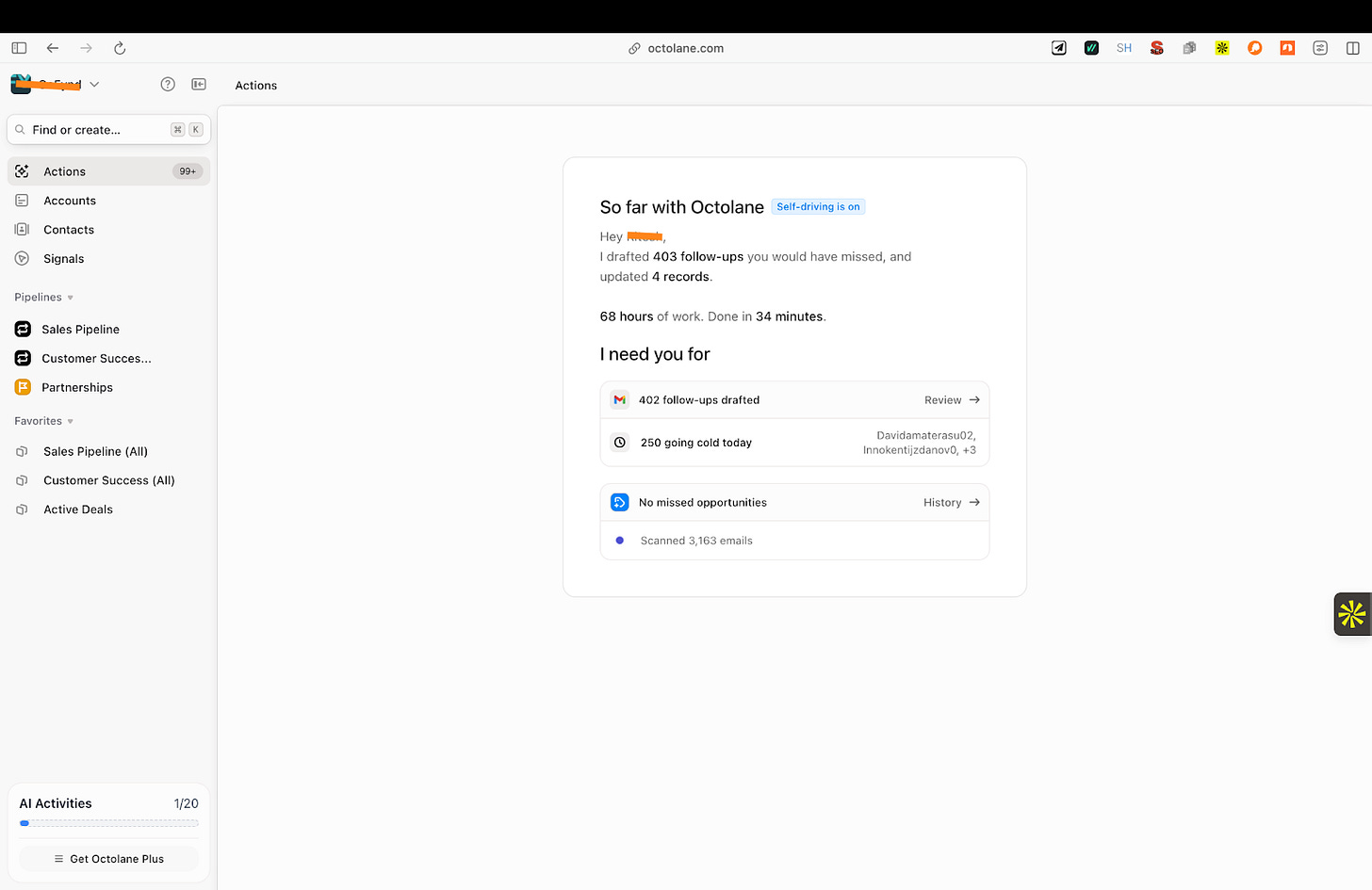

What I found interesting about Octolane is that instead of opening on a dashboard, it used my login to analyze my emails and calendar and understand the deals I was already working on.

Once that analysis was done, a lot of information was already in place. Accounts and contacts were laid out clearly, and deals came with details like ownership, close date, probability, recent interactions, and next steps already filled in. Not all of it was accurate, but it reduced the amount of manual work I would otherwise have had to do.

The email drafts also stood out. Octolane picked up context from past conversations and wrote follow-up emails based on what had already been discussed. I only needed to review the draft once before sending it directly from the tool.

It also shows deal predictions. I wouldn’t rely on them, but they give a sense of where the product is headed and how it’s trying to stay closer to day-to-day sales work.

Where it works well

Octolane works best for small sales teams where Gmail and Google Calendar are the primary systems of work, including teams that actively close and lock in deals through ongoing email and meeting-based conversations.

It’s not fully accurate, and some details still need to be checked and corrected, but the overall effort is much lower than maintaining everything by hand.

For now, it works better for simpler sales setups. If your deal stages and fields are straightforward, the tool is easier to use. Teams with complex workflows or heavily customized CRMs may find it limiting.

It works best when used as a tool that prepares information, not something you rely on blindly.

Where it falls short

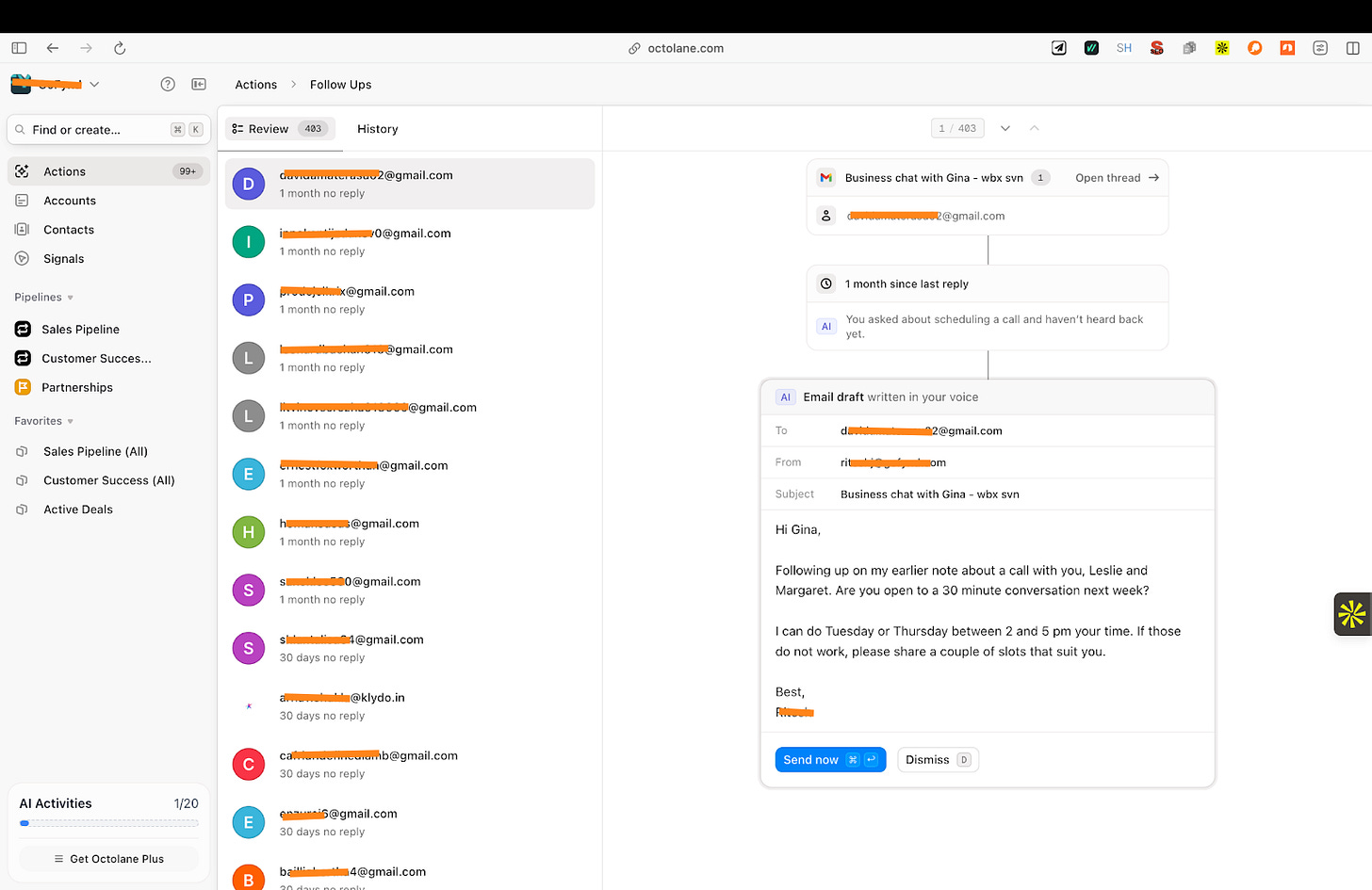

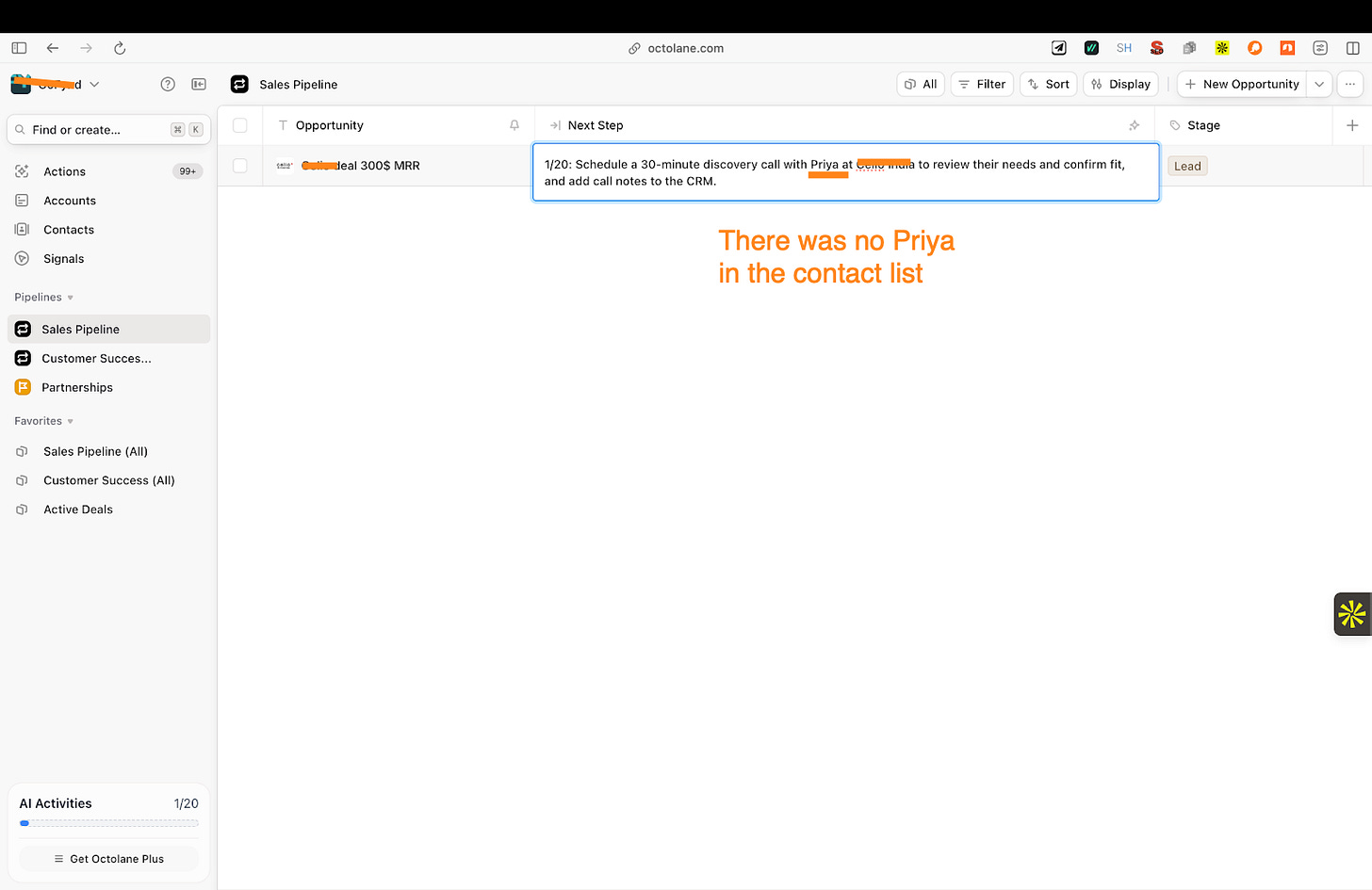

The biggest issue for me was accuracy. It doesn’t get the basics right. In my case, it created a deal with the wrong contact name, which immediately made me lose interest.

It also didn’t pull in all deals. After the analysis, many conversations and opportunities were missing, which meant the view it created wasn’t complete or accurate. That made it hard to rely on the tool to reflect everything I was working on.

I constantly felt the need to monitor it. I couldn’t depend on it blindly. I had to review the data, fix details, and sometimes add information myself, which takes away from the idea of a fully self-running CRM.

There’s also no clear review or approval flow. While drafts and data are generated quickly, there isn’t a structured way to manage reviews or validate what’s been created, especially if more people were to use it.

A sales manager I spoke to, Ritesh, rated it 2 out of 5 and described it as a basic tool. That feedback matched my experience. The idea is strong, but the execution still feels early.

What makes it different

Octolane stands out for how it updates a CRM. Most CRMs, including tools like Attio, focus on structured fields such as deal stage, value, and next steps, and depend on users to update those fields manually. Lightfield focuses on reading conversations to build context. Octolane takes a different approach. It looks at email threads and calendar meetings and tries to create or update deals, contacts, and follow-ups based on that activity.

It is built around automatic updates, not suggestions. This matters because the AI is not just recommending what to do next. It is actively creating records, moving deals forward, and drafting follow-ups using what it sees in emails and meetings.

This design makes Octolane feel less like a tool you operate and more like a system that runs in the background. Instead of asking you to log activity after the fact, it tries to capture sales activity as it happens and reflect it directly in the CRM.

My take

I like the direction Octolane is taking. Letting the CRM follow email and calendar instead of forcing people to work inside it makes sense, and when it works, it genuinely reduces some of the busywork around sales.

But right now, I don’t trust it enough to run on its own. The accuracy issues, missing deals, and lack of a proper review flow mean I have to stay involved. That limits how much time it actually saves.

I’d use Octolane as a supporting tool, not as my main CRM. It’s helpful for keeping track of conversations and reducing manual updates, but it still feels early. The idea is solid. The product needs more time to catch up.

AI in Product

Firecrawl Agent: An AI Shortcut Between Intent and Scraping Code

TL;DR

Firecrawl Agent is an AI-powered tool for extracting structured data from public websites using prompts and schemas instead of custom scraping logic. It works well for exploration and prototyping, but struggles with scale, limits, and reliability.

Basic details

Pricing: Free plan available with paid plans starting from $16/month

Best for: Developers, data teams, and product teams working with public web data

Use cases: Web scraping and crawling, structured data extraction in JSON or text, early experimentation and data validation

A lot of modern software work depends on data that lives on the open web. Product catalogs, pricing pages, listings, documentation, and content sites are all public, but not easily usable. Getting that data usually means writing custom scrapers, handling JavaScript-heavy pages, and fixing things every time a layout changes.

Firecrawl’s Agent steps into that workflow. It’s a tool designed to extract structured data from websites without forcing you to handcraft the entire scraping logic yourself. You describe what you want, point it to a URL, and choose the output format, while the system handles crawling, rendering, and extraction in the background.

What’s interesting

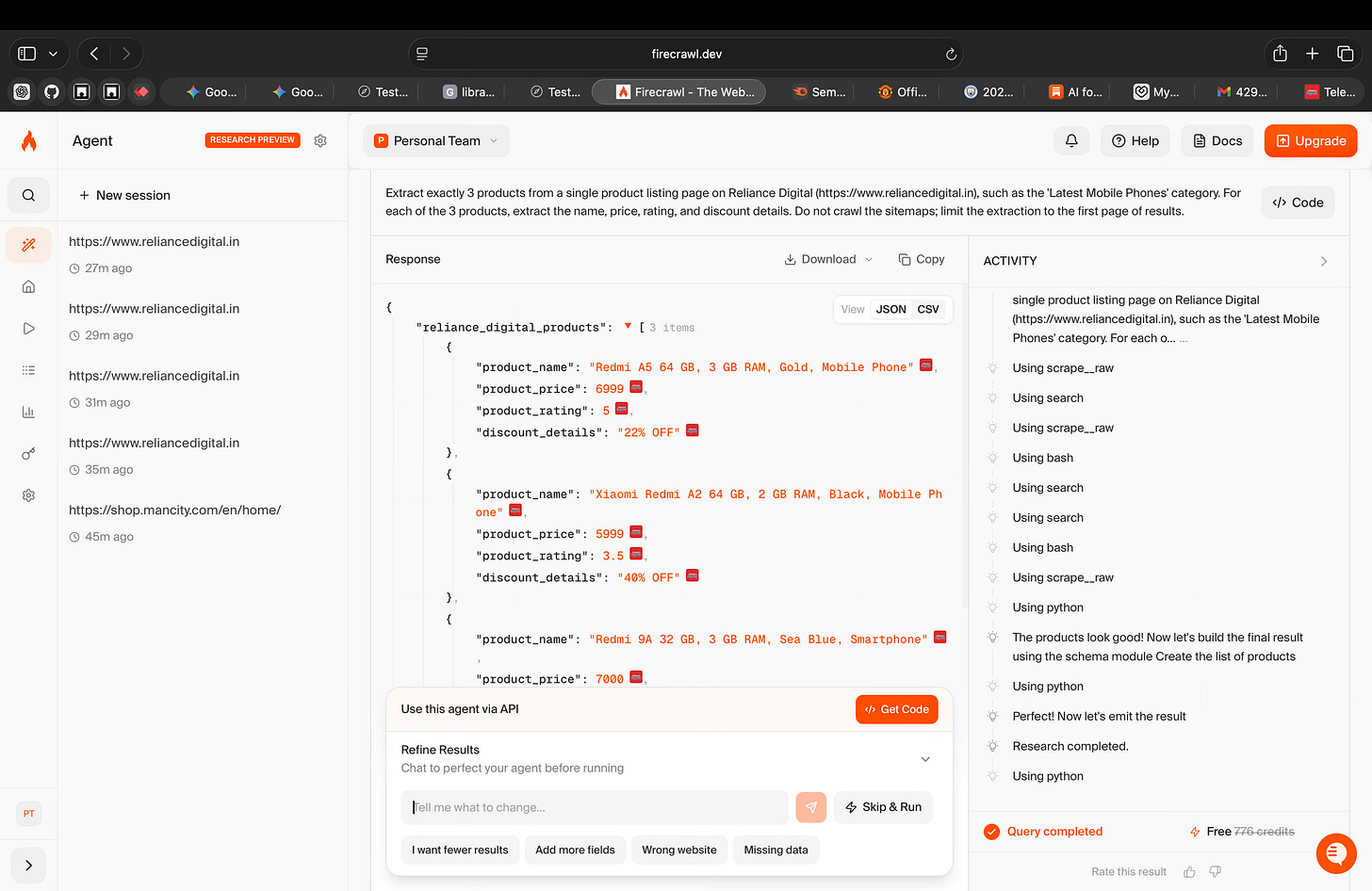

What’s interesting about Firecrawl’s Agent is how it turns web extraction into a guided process instead of a one-shot scrape.

When I ran it on the Reliance Digital website, it didn’t assume what I wanted. It asked clarifying questions, let me define the structure, and then worked toward producing data in that shape. The interaction felt more like configuring a task than writing scraping logic.

I also liked the schema-based output. Being able to define fields upfront and receive the results directly in JSON made the output immediately usable. There was no extra step of cleaning or restructuring the data after extraction, which usually takes up a lot of extra time.

Where it works well

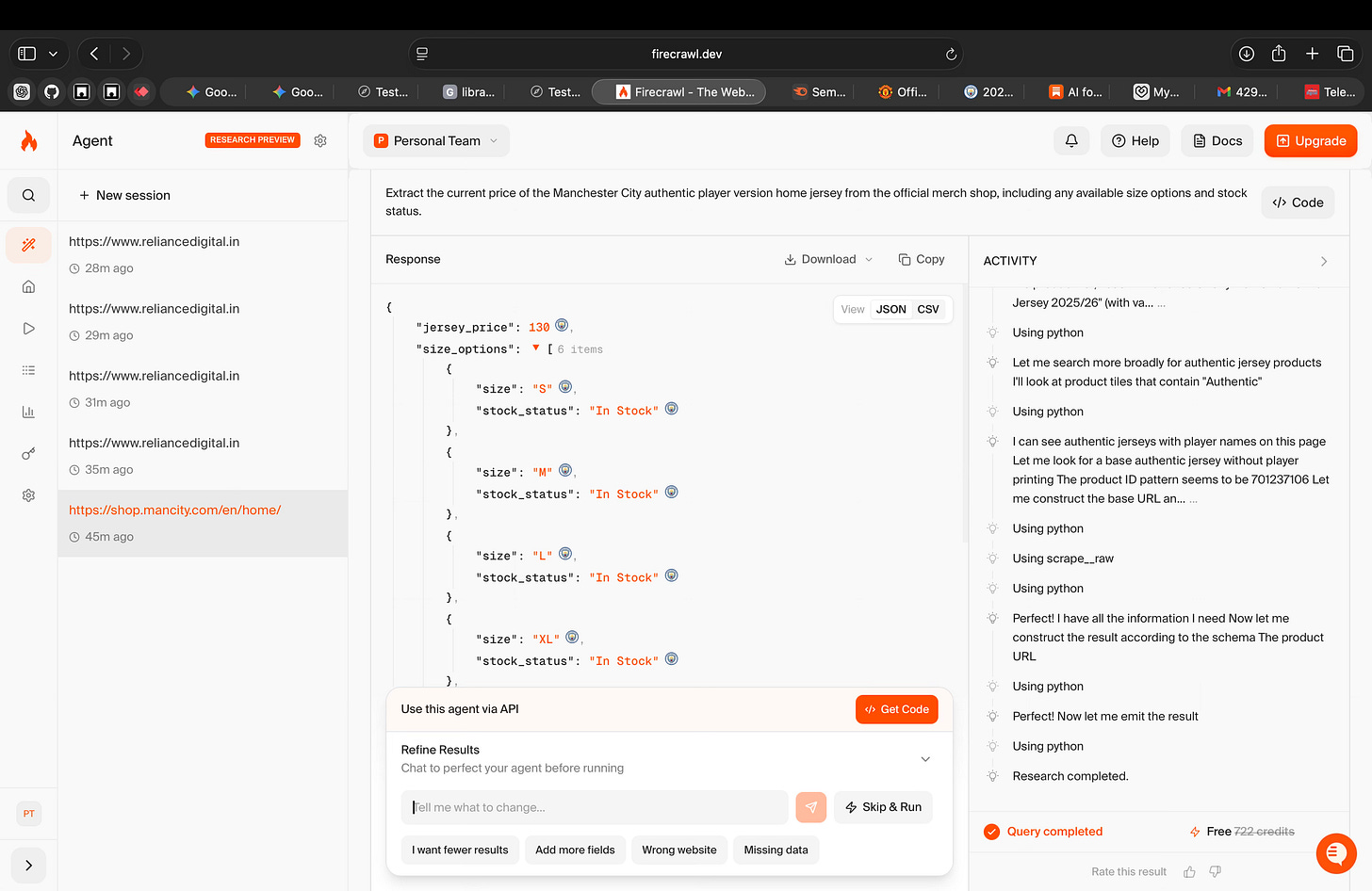

Firecrawl works well for tasks where the goal is to extract data from public websites without building and maintaining custom scraping logic.

In my experience, it was most effective for early exploration and one-off extraction tasks, where I needed to quickly test whether a site could yield usable data. I didn’t have to invest upfront time in writing or debugging code just to validate the idea.

Based on this, Firecrawl feels well suited for developers, data teams, and product teams who regularly work with public web data and want a faster way to experiment, prototype, or support internal tools. It’s especially useful when speed of setup and visibility into the process matter more than accuracy or scale.

Where it falls short

The biggest issue I faced was reliability during the first few runs. On the Reliance Digital website, the extraction did not work well initially. I had to try multiple times, change the prompt, and adjust the schema before I got usable results. This kind of trial and error is manageable for testing, but it makes the tool harder to trust for consistent use.

The token limit is another major constraint. I hit the 200k token limit very quickly, even while testing. When I tried to extract more products or run a broader crawl, the job failed. This makes it difficult to test or work with larger websites without breaking tasks into smaller parts.

I also noticed that you need to be very specific when working with bigger websites. Vague prompts don’t work well. The more complex the site, the more detailed the instructions need to be. On smaller or simpler websites, the tool works more smoothly and requires less effort.

The tool also only works with public websites. Anything behind login screens, paywalls, or restricted access is out of scope, which limits where it can be used.

What makes it different

What makes Firecrawl different isn’t that it scrapes the web. Plenty of tools already do that, and many of them do it better.

The difference is how Firecrawl uses AI.

If I compare it to tools like Selenium, Beautiful Soup, or Scrapy, those are still far more reliable once they’re set up. They’re deterministic. You write the logic, handle edge cases, and know exactly what will happen. The downside is that everything is manual. Any change on the website means more code and more maintenance.

On the other end, platforms like Apify or Diffbot handle scale and stability much better. They’re built to run large jobs repeatedly. But they also hide a lot of the process. When something breaks, you often just see a failed job, not why it failed.

Firecrawl takes a different path. It uses AI to replace hard-coded scraping logic with intent. You describe what you want, define the structure, and the agent tries to figure out how to get there. It makes decisions along the way, retries when things fail, and adapts its approach. Crucially, you can see all of this happening.

That visibility is what stands out. Firecrawl doesn’t pretend the web is clean or predictable. It shows you the mess. But that also means you’re relying on AI judgment instead of fixed rules, which introduces uncertainty.

So the trade-off is clear. Firecrawl is faster to start with and easier to experiment on, but it’s less stable and less predictable than mature tools. It’s not replacing traditional scraping or managed platforms. It’s changing how much effort you put in before you get something usable.

Whether that’s a good thing depends on how comfortable you are trading control for flexibility.

My take

Using Firecrawl changed how I think about web extraction more than how I’d actually do it today.

What it showed me is that AI can sit between intent and code. I didn’t have to decide upfront how a site should be scraped. I could start with what I wanted and see how far the tool could take me. That makes early exploration faster and less intimidating.

But it also made the limits very visible. The more complex the site, the more specific I had to be. The more data I wanted, the more fragile the process became. At that point, the AI stopped feeling like leverage and started feeling like something I had to manage.

So I don’t see Firecrawl as a replacement for scraping tools. I see it as a bridge. It helps you move from “can this work?” to “this is what would be required.” That’s a useful place for a product to exist, even if it’s not where the work ultimately ends.

For me, its value is less in the data it returns and more in the clarity it gives you early on.

AI in Design

Spacely: AI-Assisted Interior Design Iteration

TL;DR

Spacely is an AI-assisted interior design tool focused on editing and iterating on existing spaces. It supports localized changes, lighting control, and visual comparison, making it useful for early design exploration rather than final production.

Basic details

Pricing: Free plan available with paid plans starting from $15/month

Best for: Interior designers, architects, and visualization teams

Use cases: Early-stage design exploration, visual iteration and comparison, client presentations and internal reviews

Most interior design and architecture work is visual, but a lot of the effort goes into producing visuals rather than exploring ideas.

Trying out a different lighting setup, adding a piece of furniture, or changing a wall detail usually means reworking a render or regenerating an image entirely. That makes small design decisions slower than they need to be.

Spacely is an AI design tool built for working on existing spaces. It allows designers to make targeted changes, compare versions, adjust lighting, and add or remove objects without starting over each time.

What’s interesting

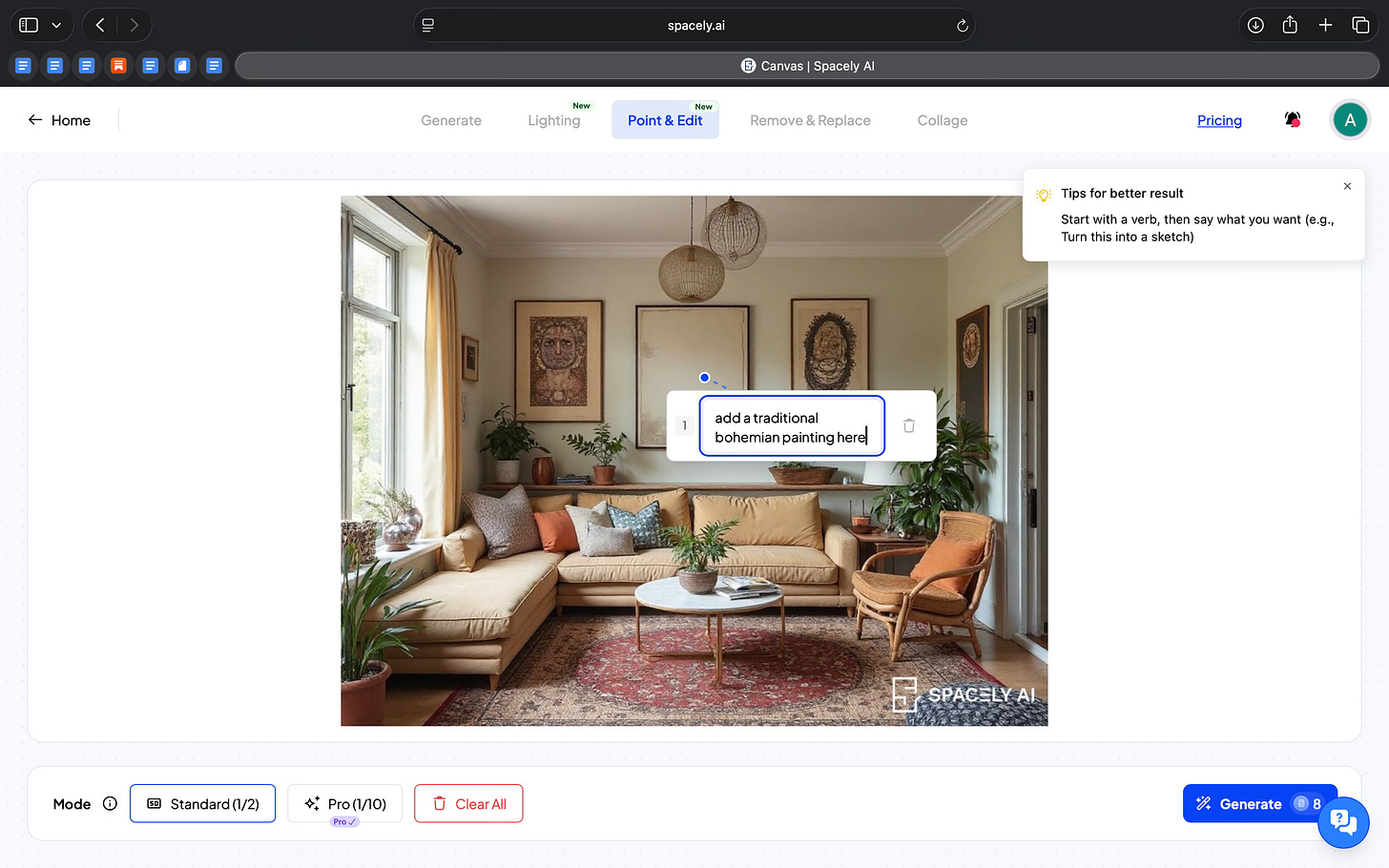

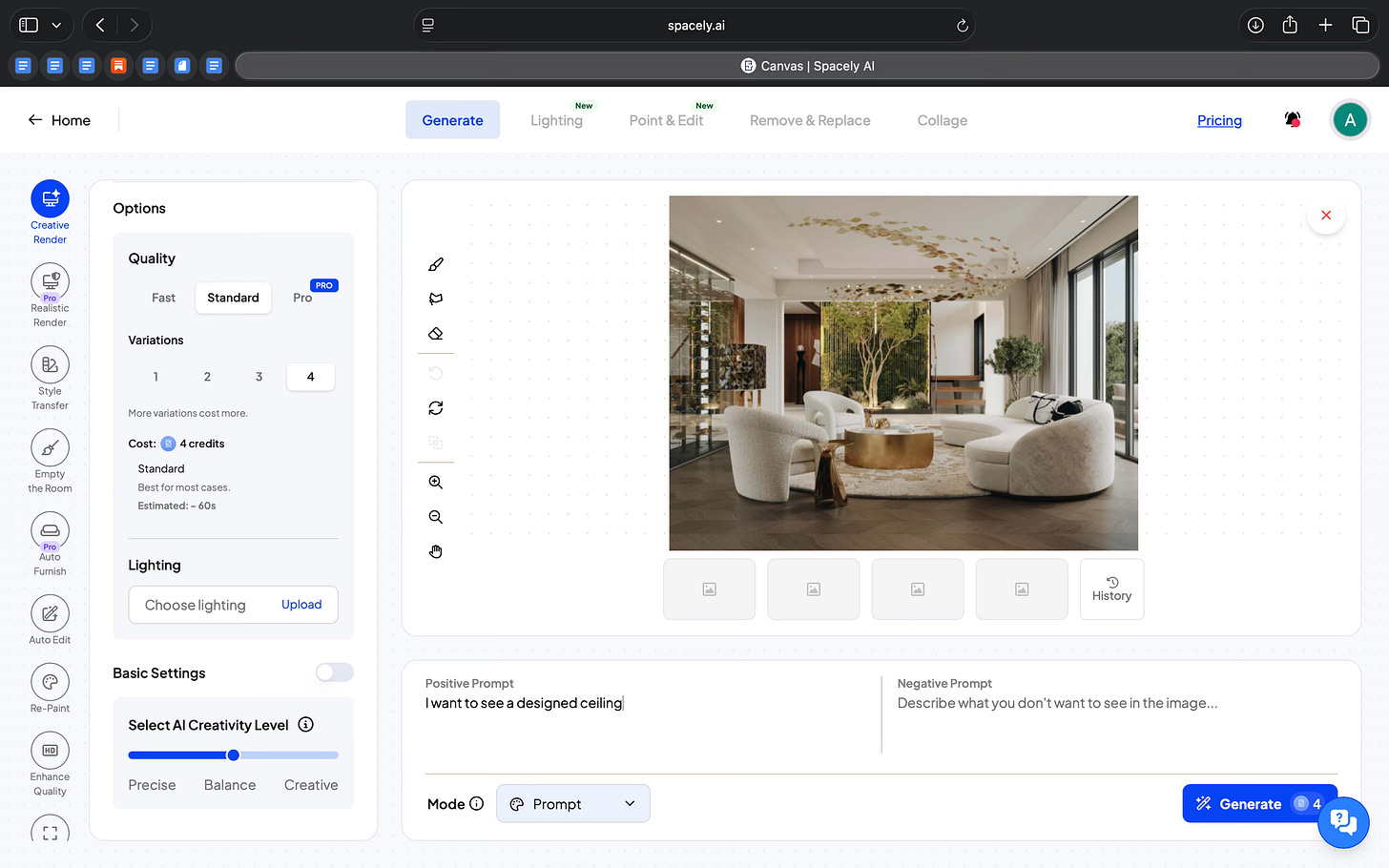

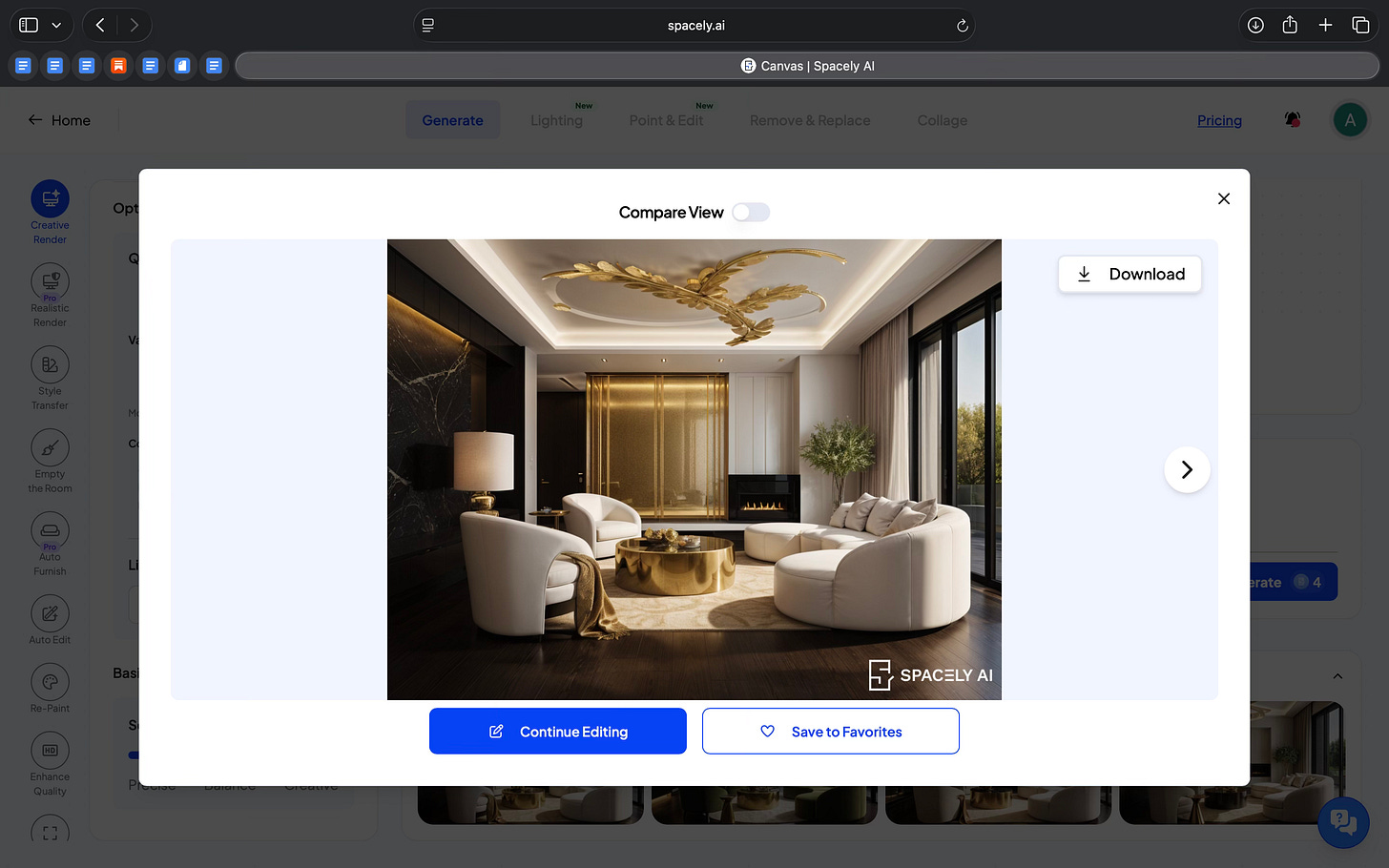

Spacely allows you to work on a specific space without forcing you to regenerate everything each time.

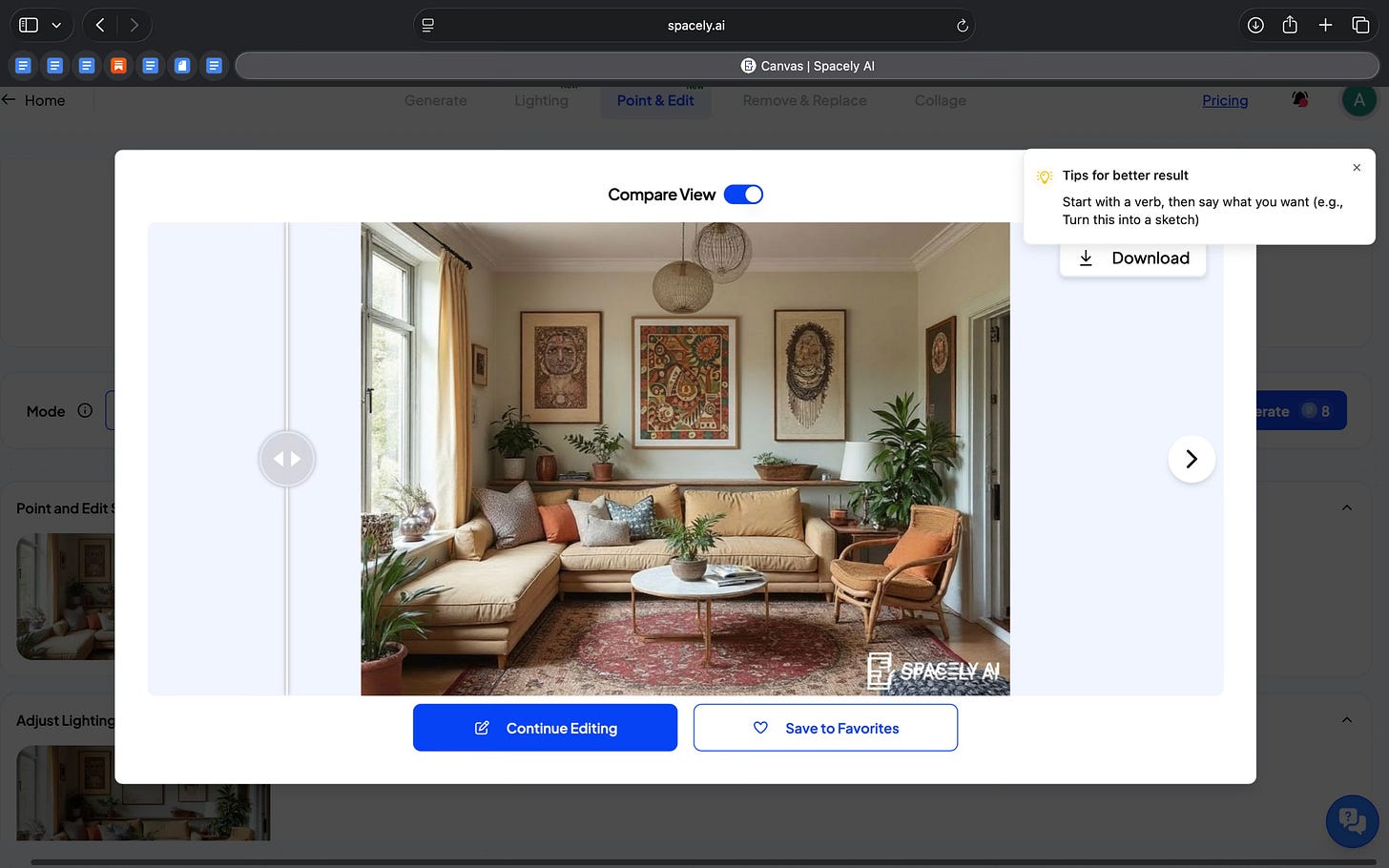

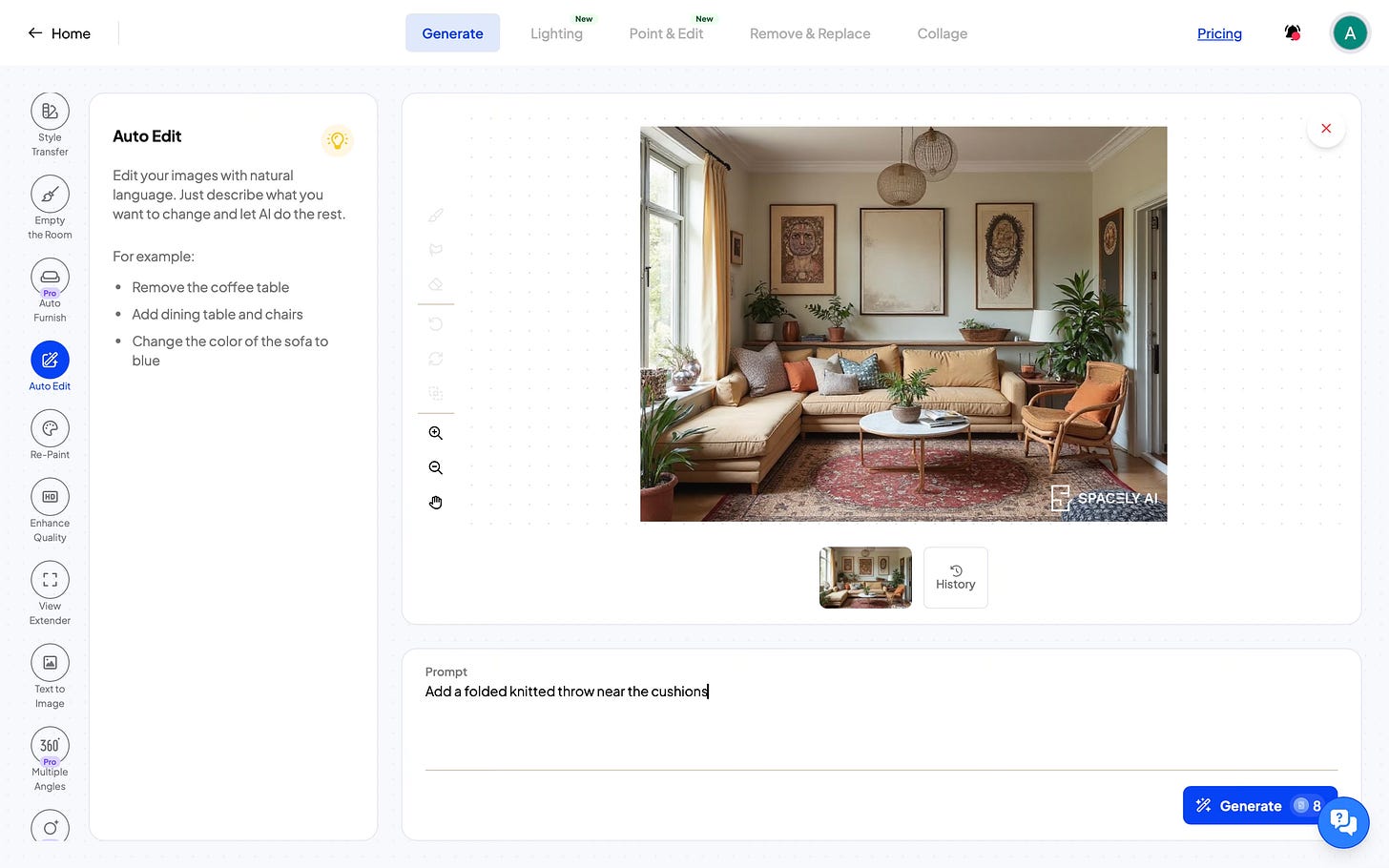

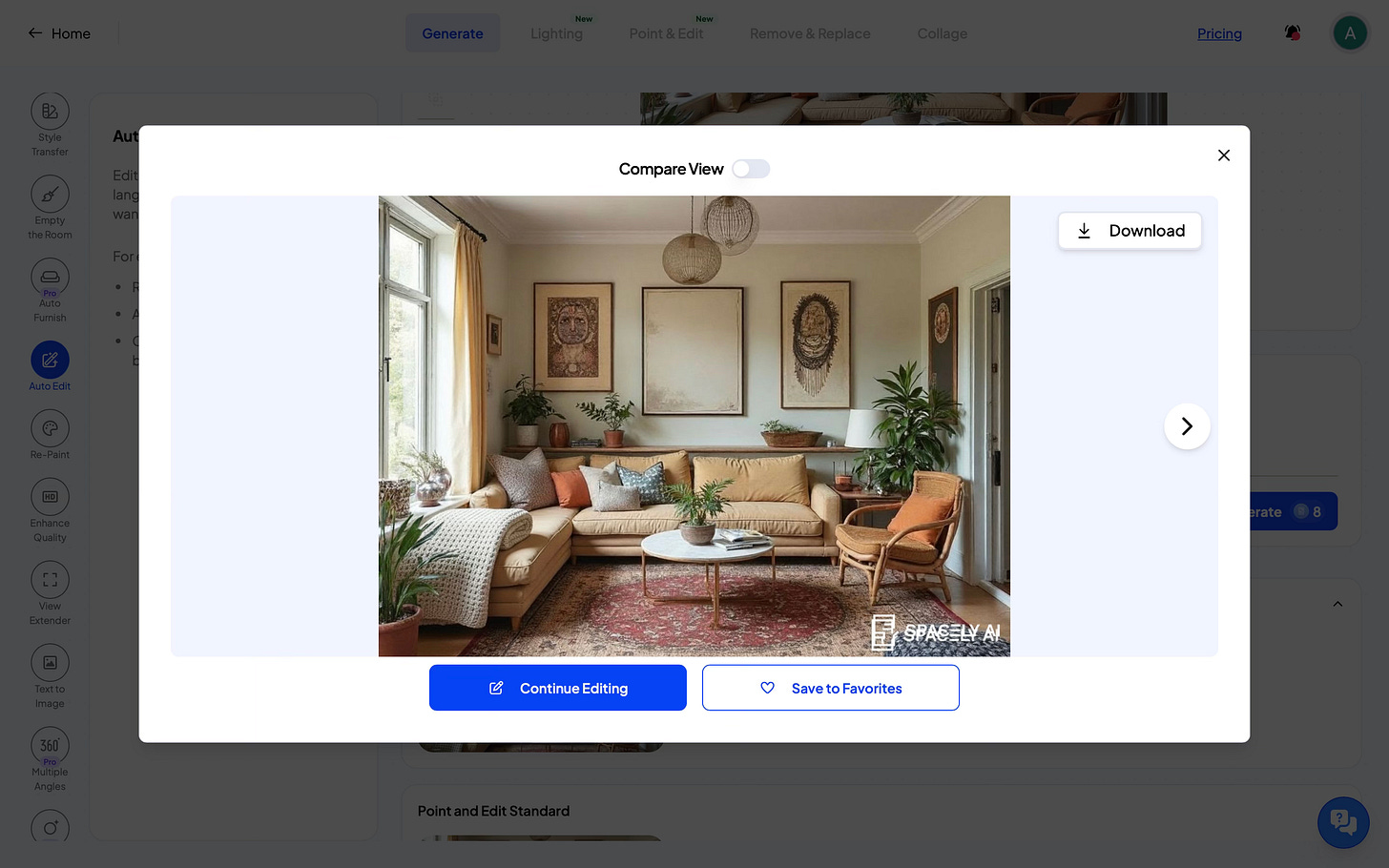

I started by working on an existing interior rather than generating a new image from scratch. From there, I could make very specific changes. Using Point & Edit, I clicked on a particular area of the image and added a traditional bohemian painting to the room. The painting appeared exactly where I clicked, and the rest of the space stayed the same.

For object-level changes, I used Auto Edit and Remove & Replace. With Auto Edit, I could describe a change in simple language, like adding a folded knitted throw near the cushions, and the tool applied that change to the image. With Remove & Replace, I could remove an existing object or replace it with something else. In both cases, the changes were limited to that object and didn’t affect the rest of the design of the room.

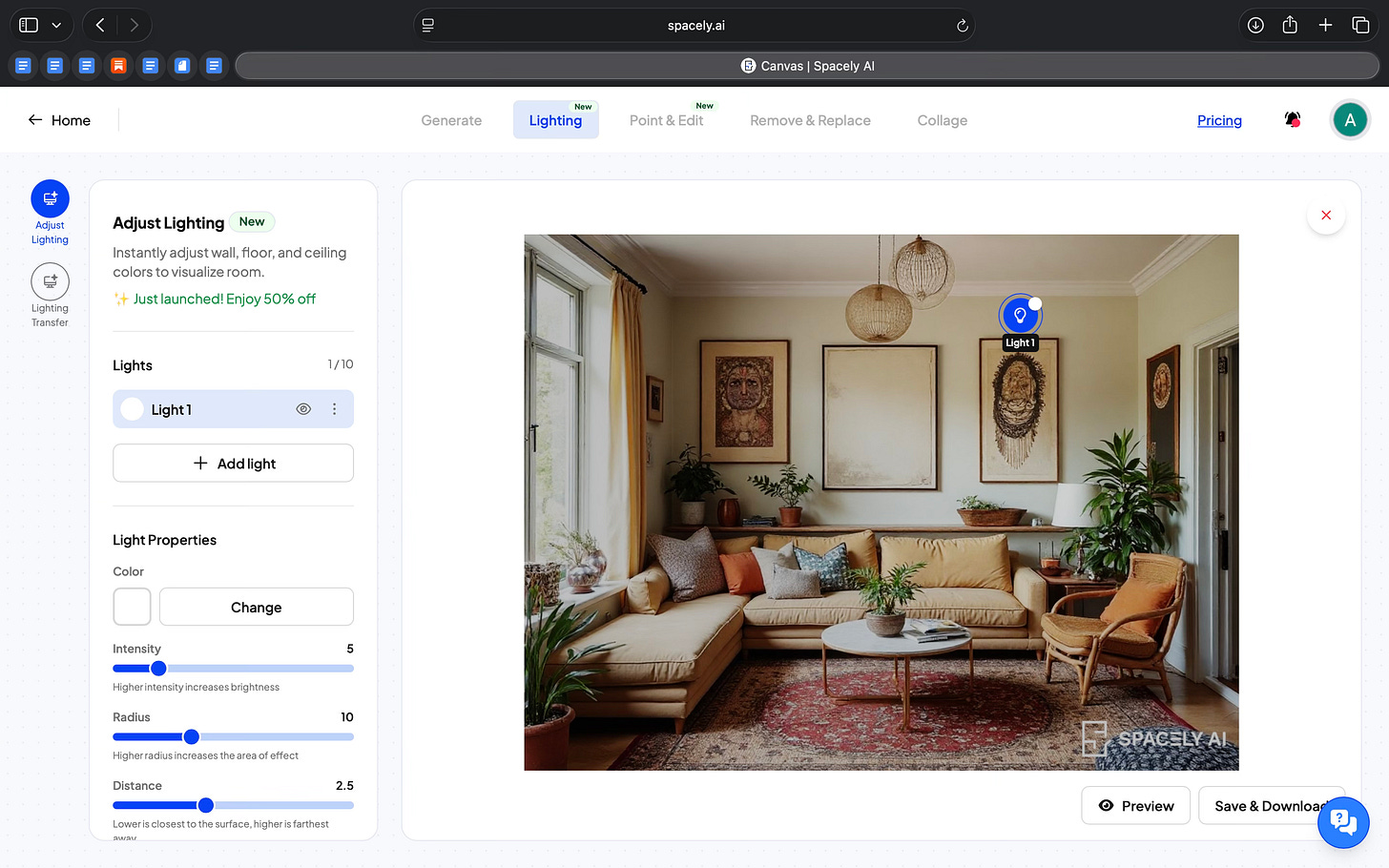

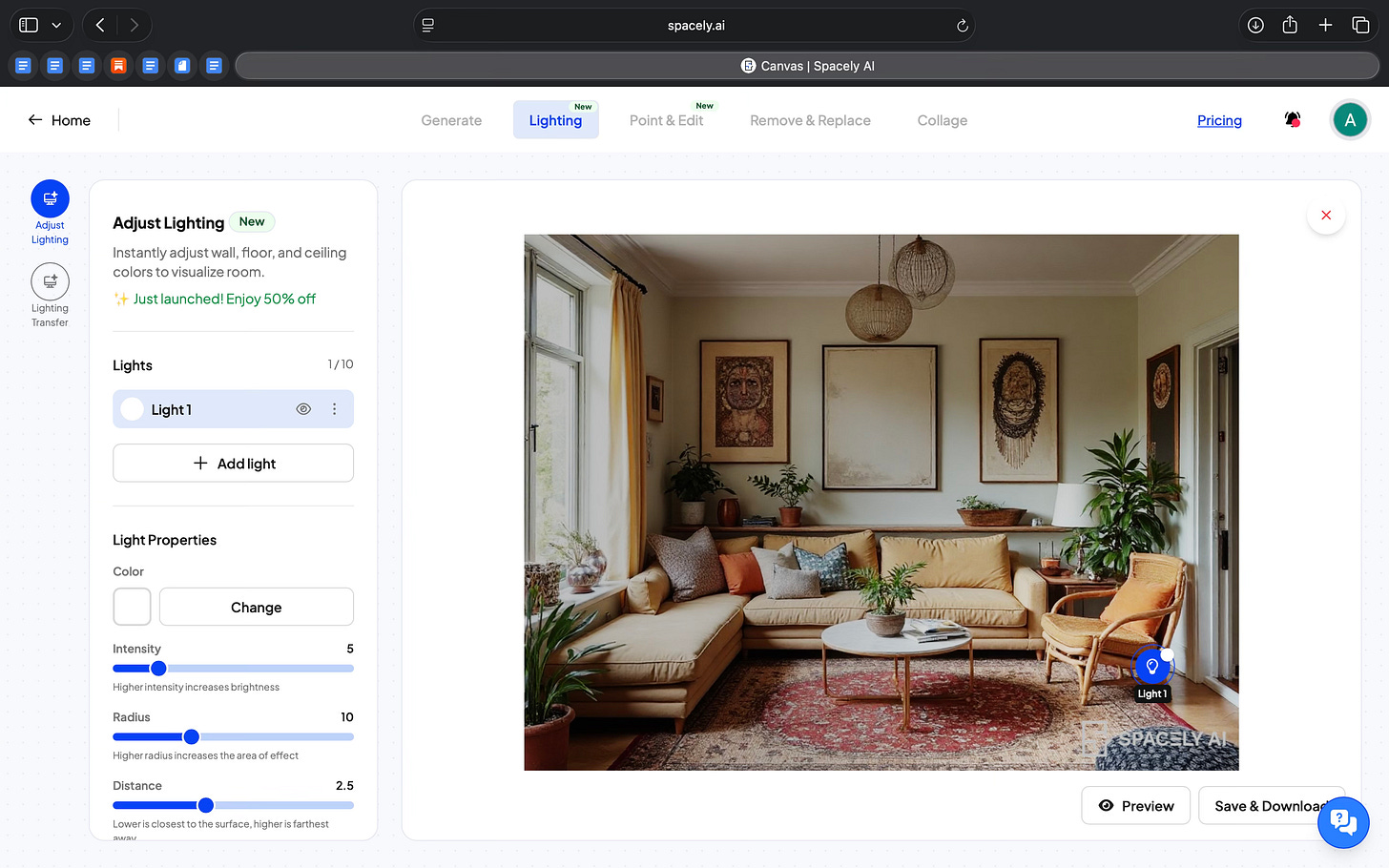

What’s more was I could control the lighting of the room. Instead of treating lighting as a single style choice, it lets you work with it in detail. I could switch between lighting presets like daylight or evening light, and I could also adjust individual light sources. Each light could be changed by color, intensity, radius, and position. This made it possible to test different moods without changing the layout or materials.

Spacely also lets you work on architectural elements like the ceiling. I could design and modify the ceiling independently. That kind of control is usually hard to get in AI-based interior tools.

I also explored the Collage mode, which works differently from prompting. Instead of asking the AI to generate objects, I could place 2D or 3D assets directly into the space from an asset library. I could move them around, resize them, and build the scene piece by piece. This felt more manual and controlled, with AI supporting the process rather than taking over.

In addition to this, Spacely offers style and space presets, which make it easier to explore different design directions easily. You can switch styles or room types without starting from scratch, which helps when you want to test multiple options.

Across all these features, the AI is embedded into specific actions instead of acting like a chatbot. The tool guides you on how to write prompts, limits the scope of changes, and keeps edits focused. What stood out to me is that Spacely lets you work in small steps, change one thing at a time, and keep refining the same space instead of committing to a final image early.

Where it works well

Spacely feels best for exploring different variations of a space rather than producing a final, locked-in render.

I feel it’s most suited for early design exploration and iteration. Basically for when you want to test multiple designs quickly, it will help you go back-and-forth without having to redesign everything each time.

It’d fit well into internal reviews, concept discussions, or early client conversations.

Where it falls short

Spacely focuses on visual exploration more than technical designing. You are only working around with images, and the controls are based on visual adjustments instead of precise measurements.

There are multiple modes and tools and it takes time to understand how to approach them.

What makes it different

When I compare Spacely to other tools in the design and visualization space, what stands out isn’t a single “better feature,” but a different way of working.

Visualization tools like Twinmotion and Lumion help designers with high-quality, production-ready renders, but they require significant setup, scene preparation, and design expertise. They are good, but they are also technical and time-intensive. Spacely doesn’t replace these tools, and it doesn’t aim for production-grade realism or interactive environments. What it brings instead is speed of iteration without heavy technical overhead.

On the other hand, generative AI image tools like Midjourney, DALL-E, or Stable Diffusion can create inspiring visuals from prompts, but they treat output as single, final images. If you want to make a specific change, like moving a lamp, adjusting lighting, or editing only the ceiling, you often have to regenerate the whole image or rely on workarounds.

In my experience with Spacely, the ability to make targeted edits using Point & Edit, Auto Edit, or Remove & Replace without disturbing the rest of the room is something prompt-only tools don’t offer.

There are also design-centric AI platforms that lean toward full automation and try to generate a complete style solution from minimal input. Spacely doesn’t try to guess the design. Instead, it lets you stay in control and make small decisions step by step, which feels closer to how designers actually work.

So the difference isn’t that Spacely does everything better. It sits in a middle ground. It is less technical and heavy than full visualization engines, more editable and controlled than prompt-only generative tools, and less automated than end-to-end design automation platforms.

My take

What stayed with me while using Spacely was the way it let me stay inside the design process instead of jumping in and out of it.

I didn’t feel like I was “generating images.” I felt like I was working on a space. Making a small change, seeing how it looked, adjusting something else, and continuing from there. That’s not something most AI design tools get right today.

This is what I feel product managers and designers building AI tools should pay attention to. Spacely doesn’t optimize for impressive outputs. It optimizes for flow. It keeps the user oriented, lets discussions build on each other, and avoids forcing a reset every time you want to explore a new idea. This pattern should apply far beyond interior design.

At the same time, I was always aware of what it is and what it isn’t. Spacely doesn’t replace professional design tools, and it’s not meant for final or technical outputs. It’s a visual thinking tool. It helps you explore, explain, and iterate, especially when ideas are still forming.

In the Spotlight

Recommended watch: The Future of Architecture: A look beyond the AI hype

Olly Thomas (Design Tech at BIG) gives a grounded view of AI in architecture: it’s not “idea magic,” it’s a force-multiplier for iteration, visualization, and the boring admin work. The upside is simple: less time rendering and formatting, more time on judgement, research, and design thinking.

The value of what we do as architects… is still the thinking… that hasn’t changed.

– Olly Thomas • ~7:43

This Week in AI

A quick roundup of stories shaping how AI and AI agents are evolving across industries

Anthropic introduces Claude as a coworker, emphasizing persistent context, tool use, and ownership of real work, not just answers.

Slack turns Slackbot into a context-aware AI agent, embedded directly in conversations and workflows where work already happens.

Google releases the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP), an open standard that enables AI agents to browse and transact across merchants, pushing commerce toward an agent-first model.

AI Out of Office

Source: Kaily AI

AI Fynds

A curated mix of AI tools that make work more efficient and creativity more accessible.

AnimateAI → An AI tool that turns text prompts into short animated videos. Useful for quick motion concepts, explainers, or lightweight social content without a full animation setup.

Meshy → An AI-powered 3D generation tool that creates models from text or images. Useful for rapid 3D ideation, asset exploration, and early-stage spatial thinking.

AI Video Generator → An AI video generation tool designed to automate video creation and transformations. Useful for producing and adapting video assets across product and marketing workflows.

Closing Notes

That’s it for this edition of AI Fyndings.

With Octolane trying to reduce the overhead of keeping CRMs updated, Firecrawl helping teams explore web data before committing to full pipelines, and Spacely making design iteration more fluid, this week pointed to a shared shift. AI is moving closer to the actual work, not by replacing people, but by taking on the repetitive effort that slows progress down.

Thanks for reading. See you next week with more tools, patterns, and ideas that show how AI is quietly reshaping how we work across business, product, and design.

With love,

Elena Gracia

AI Marketer, Fynd